The Art of Observation in the Edo Period (1600–1868) [part one]

Between the late thirteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, Japan was ruled by a series of shoguns, feudal military lords who were the holders of actual power, despite the emperor’s role in appointing them. Emperors were important cultural figures despite holding only titular power. In 1600, after a series of civil wars, the Tokugawa family seized control of the government and established the Tokugawa Shogunate. Their nearly two-and-a-half-century rule was known as the Edo period, in reference to their capital city (now called Tokyo).

The Edo period ushered Japan into an era of wealth and relative peace, during which the arts flourished. Artists found a new audience in prosperous city-dwellers who had an appetite for images of daily life—both quiet domestic scenes and lively depictions of festivals and pilgrimages. Urban audiences also were drawn to images of scenic spots and travel pictures, a nod to the rise of tourism in a country once plagued by frequent warfare. Consumers of Edo art ranged from rich merchants who could afford sumptuous multi-panel screens to working-class citizens who fueled the market for inexpensive woodblock prints. As the screens, paintings, and prints on display demonstrate, a common challenge for Edo period artists was the creation of images that required keen observation of the world around them.

-

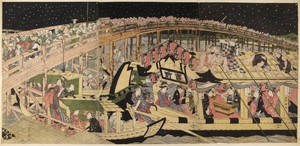

Watching Fireworks on the River (Ryōgokubashi hanabi 両国橋花火)

Watching Fireworks on the River (Ryōgokubashi hanabi 両国橋花火), ca. 1815 [Bunka 2]

Watching Fireworks on the River (Ryōgokubashi hanabi 両国橋花火), ca. 1815 [Bunka 2]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

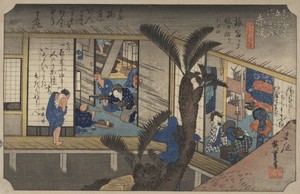

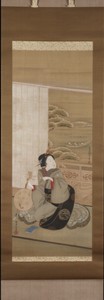

Akasaka: Inn with Serving Maids (Akasaka, ryosha shōfu no zu 赤坂 旅舎招婦ノ図), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Akasaka: Inn with Serving Maids (Akasaka, ryosha shōfu no zu 赤坂 旅舎招婦ノ図), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Akasaka: Inn with Serving Maids (Akasaka, ryosha shōfu no zu 赤坂 旅舎招婦ノ図), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

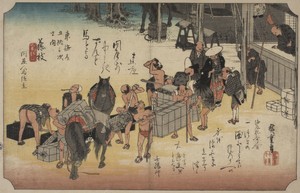

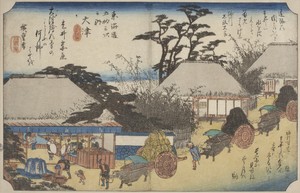

Fujieda: Changing Porters and Horses (Fujieda, jinba tsugitate 藤枝 人馬継立), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Fujieda: Changing Porters and Horses (Fujieda, jinba tsugitate 藤枝 人馬継立), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Fujieda: Changing Porters and Horses (Fujieda, jinba tsugitate 藤枝 人馬継立), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

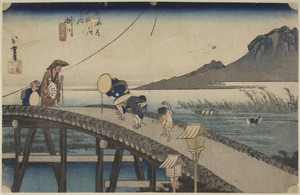

Kakegawa: View of Akiba Mountain (Kakegawa Akiba-san enbō 掛川 秋葉山遠望), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Kakegawa: View of Akiba Mountain (Kakegawa Akiba-san enbō 掛川 秋葉山遠望), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Kakegawa: View of Akiba Mountain (Kakegawa Akiba-san enbō 掛川 秋葉山遠望), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

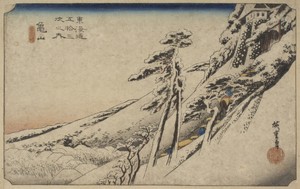

Kameyama: Clear Weather after Snow (Kameyama, yukibare 亀山 雪晴), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Kameyama: Clear Weather after Snow (Kameyama, yukibare 亀山 雪晴), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Kameyama: Clear Weather after Snow (Kameyama, yukibare 亀山 雪晴), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

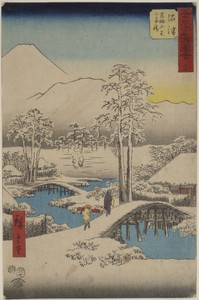

No. 13, Numazu: Fuji in Clear Weather after Snow, from the Ashigara Mountains (jūsan, Numazu, Ashigarayama Fuji no yukibare 十三 沼津 足柄山不二雪晴), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会)

No. 13, Numazu: Fuji in Clear Weather after Snow, from the Ashigara Mountains (jūsan, Numazu, Ashigarayama Fuji no yukibare 十三 沼津 足柄山不二雪晴), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), 1855 [Ansei 2], 7th month

No. 13, Numazu: Fuji in Clear Weather after Snow, from the Ashigara Mountains (jūsan, Numazu, Ashigarayama Fuji no yukibare 十三 沼津 足柄山不二雪晴), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), 1855 [Ansei 2], 7th month

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

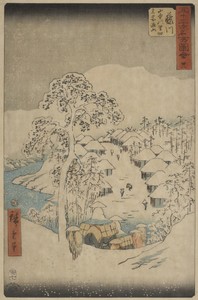

No. 38, Fujikawa: Mountain Village, Formerly Called Mount Miyako (Fujikawa, sanchū no sato kyūmei Miyakoyama 三十八 藤川 山中の里旧名都山), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会)

No. 38, Fujikawa: Mountain Village, Formerly Called Mount Miyako (Fujikawa, sanchū no sato kyūmei Miyakoyama 三十八 藤川 山中の里旧名都山), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), 1855 [Ansei 2], 7th month

No. 38, Fujikawa: Mountain Village, Formerly Called Mount Miyako (Fujikawa, sanchū no sato kyūmei Miyakoyama 三十八 藤川 山中の里旧名都山), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), 1855 [Ansei 2], 7th month

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

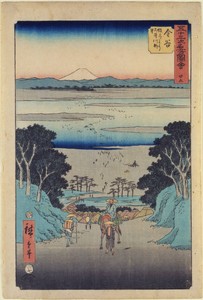

Kanaya: View of the Ōi River from the Uphill Road (Kanaya, Sakamichi yori Ōigawa chōbō 金谷 坂道より大井川眺望), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会)

Kanaya: View of the Ōi River from the Uphill Road (Kanaya, Sakamichi yori Ōigawa chōbō 金谷 坂道より大井川眺望), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), ca. 1855

Kanaya: View of the Ōi River from the Uphill Road (Kanaya, Sakamichi yori Ōigawa chōbō 金谷 坂道より大井川眺望), from the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-three Stations” (Gojūsan tsugi meisho zue 五十三次名所図会), ca. 1855

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

Miya: Festival of the Atsuta Shrine (Miya, Atsuta shinji 宮 熱田神事), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Miya: Festival of the Atsuta Shrine (Miya, Atsuta shinji 宮 熱田神事), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Miya: Festival of the Atsuta Shrine (Miya, Atsuta shinji 宮 熱田神事), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

Ōtsu: Hashirii Teahouse (Ōtsu, Hashirii chaya 大津 走井茶屋), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Ōtsu: Hashirii Teahouse (Ōtsu, Hashirii chaya 大津 走井茶屋), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Ōtsu: Hashirii Teahouse (Ōtsu, Hashirii chaya 大津 走井茶屋), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

Shōno: Driving Rain (Shōno, hakuu 庄野 白雨), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内)

Shōno: Driving Rain (Shōno, hakuu 庄野 白雨), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Shōno: Driving Rain (Shōno, hakuu 庄野 白雨), from the series “Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō” (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi no uchi 東海道五十三次之内), ca. 1833–34 [Tenpō 4–5]

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese -

View of the Sumida River (Sumida shukukei 墨水縮景)

View of the Sumida River (Sumida shukukei 墨水縮景), ca. 1850s

View of the Sumida River (Sumida shukukei 墨水縮景), ca. 1850s

Edo period, 1615–1868

Japanese

- Page 1

- ››