de Kooning and the New York School

When the Dutch-born American artist Willem de Kooning arrived in New York in 1927, the city was in the midst of dynamic, multicultural growth that was without parallel in Europe. He soon connected with a circle of artists who were interested in assimilating European modernist idioms into a style of painting that reflected the unique energy of the American experience. De Kooning befriended Arshile Gorky, a fellow émigré painter whose fluid, Surrealist-inspired, figure-based abstractions had a profound influence on de Kooning and his generation throughout the 1930s and ’40s.

By the 1930s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art had become one of the leading art centers in the world. The museum’s interest in modern art was limited, but New York artists learned of current European avant-garde developments through the opening of new institutions: the Gallery of Living Art (1927–42), The Museum of Modern Art (1929), the Museum of Non-Objective Art (now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1939), and Peggy Guggenheim’s short-lived but influential Art of This Century Gallery (1942–47). New York institutions, exhibitions, and commercial galleries provided opportunities for artists to absorb a wide range of historical and multicultural influences, leading some to feel a moral imperative to their role in the creative arts.

The fecundity of these multiple influences gave rise to an informal group of American artists who had turned away from the regionalist and social realist subjects that were popular in the 1930s. In the 1940s these artists began painting in a variety of Abstract Expressionist styles that were inspired by universal themes and archaic myths, executed on a heroic scale that seemed appropriate to the global cataclysm of World War II and its aftermath. Collectively called the New York School, these artists were championed in a variety of magazines and other publications by two influential, but often competing, cultural critics. Harold Rosenberg advocated for the psychological authenticity of individualism, claiming that the canvas was an arena in which the artist engaged in a cathartic experience he termed “action painting,” seen in the work of de Kooning, Pollock, Pousette-Dart, Guston, and Kline. Clement Greenberg argued that the avant-garde was a product of enlightenment, an inevitable revolution against false sentiment and illusion in art, favoring abstract principles specific to each medium, as typified by the work of de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko, Newman, Reinhardt, Frankenthaler, and David Smith. Despite their differences, both critics agreed that the paintings of de Kooning and Pollock heralded a milestone in postwar American culture, and proclaimed that New York had now become the capital of modern art.

Calvin Brown

Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings

-

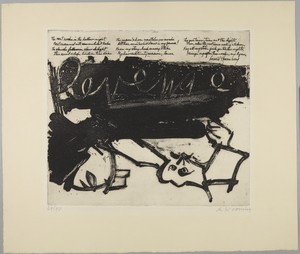

Revenge

Revenge, 1960

Revenge, 1960 -

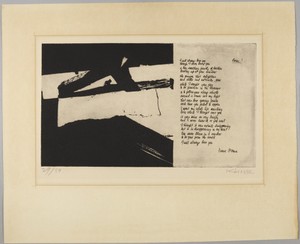

Poem

Poem, 1960

Poem, 1960 -

Untitled

Untitled, 1964

Untitled, 1964 -

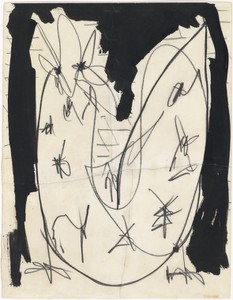

Hen

Hen, 1950

Hen, 1950 -

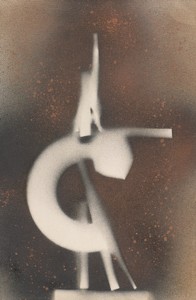

Study for Spanish Elegies

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957 -

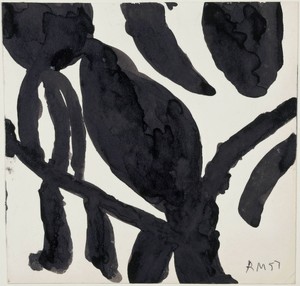

Study for Spanish Elegies

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957 -

Study for Spanish Elegies

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957

Study for Spanish Elegies, 1957 -

Untitled

Untitled, 1959–60

Untitled, 1959–60 -

Untitled

Untitled,

Untitled,

- ‹‹

- Page 2