Surface Layer: The Logic of Collage

In honor of Taiye Idahor, the 2019 Sarah Lee Elson, Class of 1984, International Artist-in-Residence, the Princeton University Art Museum presents Surface Layer: The Logic of Collage, an installation exploring the potential of the collage aesthetic—the layering of multiple elements, media, and techniques within a single work—for the discussion of identity and difference through the themes of adornment, absence, and abstraction.

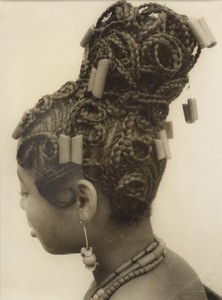

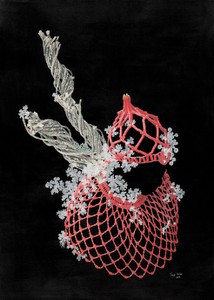

Idahor’s multimedia practice combines drawn and collaged photographic elements to reflect on the historical and contemporary status of women in Nigeria, and, more broadly, on the shifting position of women within an increasingly globalized society. In Bosede, from her Ivie series, she references the coral beads traditionally used to create the headdresses, jewelry, and regalia worn by royalty of the Benin Kingdom (1180–1897)—and more recently by brides (as documented in the photographs of Nigerian women taken by J.D. 'Okhai Ojeikere.) Ivie translates to both “beauty” and “beads” in the Bini (Ẹ̀dó) language, and Idahor plays upon this confluence.

Idahor photographs women adorned with plastic replicas of coral beads that are made in China and shipped to Nigeria for sale. The artist then digitally removes each woman’s body from the photographed image. Now doubly replicated—reproduced in plastic and also photographically—the pictures of beads are cut out and collaged onto painted paper, defining the contours of an absent female body, a reference to the oft-vacant role of the iyoba (queen mother), a powerful political position occupied by the mother of the oba (king) of Benin. Idahor’s representation of imitation coral beads highlights the fact that these adornments have become shorthand for women’s social power (or lack thereof) in Nigeria. Because replica beads are now mass-produced abroad and shipped globally, their presence reflects the conflict between heritage and contemporary culture.

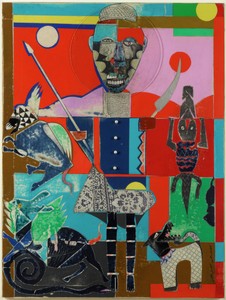

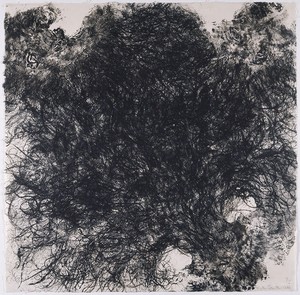

Romare Bearden also references the history of the Benin Kingdom, using reclaimed newspaper clippings, textile scraps, and other found materials, along with a photograph of a brass sculpture depicting an oba, layering African iconography into his collaged evocation of black identity. Wangechi Mutu reflects on the fragmentation of the black female form, combining watercolor and found photographs from scientific and ethnographic magazines. The body in each of these eight collages has been subjected to considerable deformation, an effect that suggests violent abuse as well as exuberant jubilation. Kiki Smith creates an abstracted self-portrait through partial imprints of her features, rolling plaster casts and rubber molds of her face and photocopies of her swirling hair to create a lithograph composed of intertwined, exploding lines.

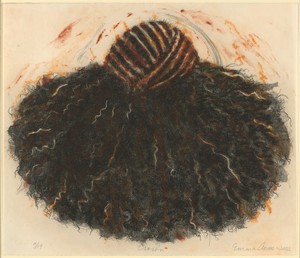

The theme of hair as adornment and as a stand-in for identity recurs in several of these works. In addition to Smith’s photocopies and Idahor’s photographs of braided coils of newspaper, Emma Amos depicts a woman facing away from the viewer, her plaited hair and riotous curls functioning as a corporeal sign of black female femininity. In Joy Gregory’s cyanotype, the role of the weave as an adornment is evoked by the undeveloped area of the print left behind where the artificial ponytail has been removed. Ellen Gallagher takes her inspiration from a series of advertisements published in African American magazines after World War II. Products such as wigs, skin creams, and hair pomades (actual dollops of which adorn the heads seen here) offered a culturally defined vision of beauty that is inextricably intertwined with the politics of race.

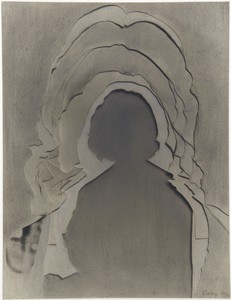

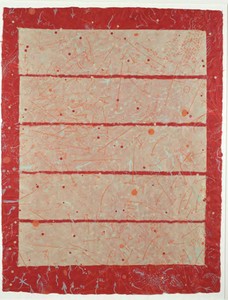

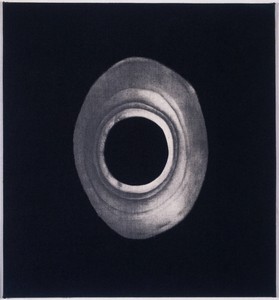

Howardena Pindell’s ostensibly abstract composition—featuring lithography, etching, and punched-out and collaged dots on five strips of buff Japanese rice paper—hides within itself a series of personal references: the crepey paper evokes skin while the red dots may allude to her childhood memory of a root-beer stand where she and her father were given mugs marked with red circles. Naomi Savage repeats the absent figure of a seemingly female form torn from paper that is then reproduced through the photograph. Lee Bontecou’s enigmatic double layer screenprint, featuring one of her characteristic black holes and the image from a lithographic stone she repeatedly reproduced across multiple print processes, refuses interpretation, paralleling the artist’s withdrawal from participation in the art market by not exhibiting or selling her work for three decades.

Together, the works in this installation compel the viewer to reflect not only on the layers of meaning that are presented but also on those that are withheld. Fragmentation and absence represent not a lack but a space into which one is welcomed to reflect upon and reconstruct that which is missing, to contemplate how such lacunae bring to the surface questions about race and gender.

-

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles, ca. 1970

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles, ca. 1970 -

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles, ca. 1970

Untitled, from the series Hairstyles, ca. 1970 -

Bosede

Bosede, 2018

Bosede, 2018 -

Harley's Halo

Harley's Halo, 1980, printed 1981

Harley's Halo, 1980, printed 1981 -

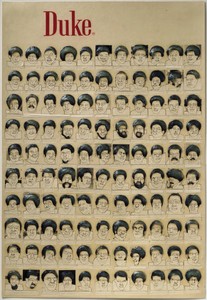

Duke

Duke, 2004

Duke, 2004 -

Chorus Line

Chorus Line, 2008

Chorus Line, 2008 -

Moon and Two Suns

Moon and Two Suns, 1971

Moon and Two Suns, 1971 -

Kyoto: Positive/Negative

Kyoto: Positive/Negative, 1980

Kyoto: Positive/Negative, 1980 -

Crown

Crown, 2002

Crown, 2002 -

Untitled

Untitled, 1967

Untitled, 1967 -

Long Black Gloss Ponytail #3 from the portfolio "Z15 (30 x30)" 2003

Long Black Gloss Ponytail #3 from the portfolio "Z15 (30 x30)" 2003, 2003

Long Black Gloss Ponytail #3 from the portfolio "Z15 (30 x30)" 2003, 2003 -

Untitled

Untitled, 1990

Untitled, 1990