Howard Russell Butler's Notebooks: Butler's Methodology

Laura Valenza, campus collections, Princeton University Art Museum

The technique of expression must have a scientific basis, even though the subject of the picture may be highly imaginary, and the artist an idealist under the sway of his imagination.

–Howard Russell Butler, from the preface to his book Painter and Space: Or, The Third Dimension in Graphic Art (1923)

Because the totality of a solar eclipse never lasts longer than seven minutes and thirty-one seconds, Butler needed to develop a method of visually recording the eclipse quickly. He was no stranger to “shorthand” sketching, and, with lots of preparation, he adapted his methodology for the solar eclipse. His notebooks and essays include detailed records on the development of his methodology, how he practiced and prepared for the eclipse, and the sketches resulting from the eclipse expedition. Though the original notebooks have not yet been found, Butler’s book on his painting theories, Painter and Space: Or, The Third Dimension in Graphic Art, fortunately includes snapshots of his sketches and notes with detailed descriptions of his process and practices.

Preparation:

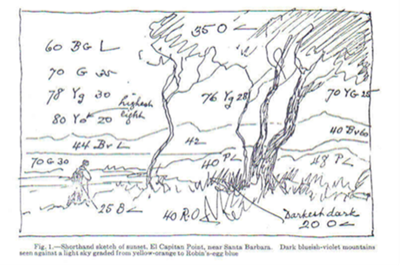

Butler developed his shorthand painting technique even before he began the solar eclipse paintings. He found a brief notation approach useful to capturing other transient effects in nature, such as the colors of the clouds or the aurora. Below, his shorthand method is outlined and exhibited in a sample sketch.

Excerpted from “Painting Eclipses and Lunar Landscapes:"

- The artist regards his subject as composed of a limited number of what he calls masses, in each of which there is a general uniformity of value, i.e., of the position of the mass on the scale of brightness—or the scale from black to white.

- First.—Quickly drawing the outline of the masses.

- Second.—Writing in, on each mass, the formula of its color.

- Third.—Locating accurately the points of highest and lowest value.

- Fourth.—If time permits, subdividing the masses.

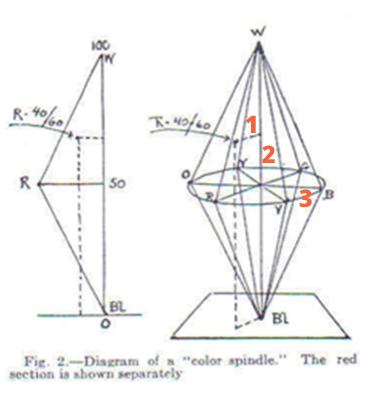

Typically, according to color theory, color has three constants: brightness (or value), hue, and saturation (or chroma). In order to make accurate notes of the colors while painting, Butler needed shorthand notations to indicate the three constants for the different “masses,” or patches of color. Butler based his color formulas on the color spindle shown below.

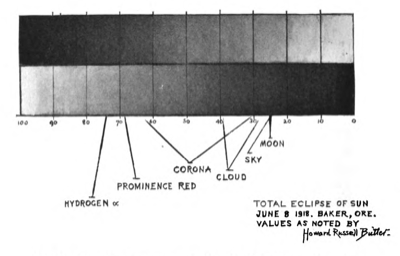

Below is Butler’s scale of brightness values, showing the brightest and darkest colors of his eclipse paintings, from the hydrogen gases at the brightest to the moon at the darkest.

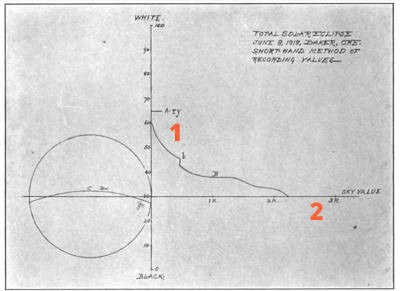

The diagram on the left shows the moon. The curve represents the varying depth of shadow. The diagram on the right shows the value of the corona as it radiates out and dissipates into the sky

A Sitting with the Eclipse, 1918

The table below shows Butler’s technique for capturing the solar eclipse. It breaks down how he spent the 112 1/10 seconds of his first eclipse sitting, in 1918. Butler notes in his general approach to this technique that as his last step in the process, should there be a little extra time, he would further divide the general "masses" he had outlined in his sketch. He writes that he “tacked it [the time chart] alongside the easel” so as to be able to follow his own instructions as a Navy officer monitored a stopwatch and called out the checkpoints in ten- or twenty-second increments. As you can see in the chart, Butler did not color in the sketch. Instead, he used color theory notations to record the value and color of the different components of the sketch, such as the moon, sky, and corona. This technique resembles a paint-by-number project, and the sketches, in addition to photographs, essentially served as guides to the later paintings. (from Painter and Space and Painting Eclipses and Lunar Landscapes)

| Note value and color of sky | 10 seconds |

| Draw value line on moon | 10 seconds |

| Note colors of moon | 10 seconds |

| Draw outline of corona | 20 seconds |

| Use Zeiss binoculars | 20 seconds |

| Record position of prominences | 10 seconds |

| Note color and value of prominences | 10 seconds |

| Note color and values of corona | 20 seconds |

Putting It All Together: The Final Sketches

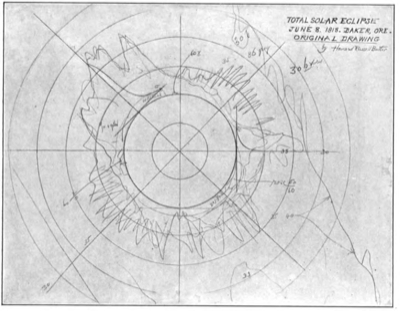

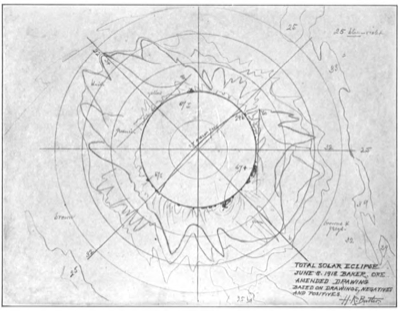

Butler’s final sketches are the culmination of his studies in color and time management. You can see the axes and grids which allowed him to create the proper scale of the eclipse and its corona as well as the outlines of the masses, filled in with their respective color formulas. The first sketch shows what he captured during the eclipse, and the second shows additional notes made after he was able to look at the photographs taken on the expedition.

Butler, Howard Russell. “Painting Eclipses and Lunar Landscapes.” Natural History v26 (4), pp. 356-362. © American Museum of Natural History, 1926.

Hear an audio re-creation of Butler's 1918 lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“The Eclipse occurred within a second of the time astronomers had calculated for it, and I was told I would have just 112 seconds in which to make the picture. I kept hoping that their calculations might be wrong and that it would take longer, because under ordinary circumstances, the kind of picture I wanted to paint, would have taken from ten to twelve sittings. I knew I should have to devise some swift system, therefore, and the first one I hit upon was the muffin-pan method. By this, I planned to have half-a-dozen panels the color the sky was to be, with dishes filled with the corona colors besides me, and to grab the colors and paint the corona as best I could. But the more I practiced with this plan the less I liked it, and finally I gave it up entirely for an old method I had used when painting clouds in landscapes before.

This was a system based on the color values of pigments. The value of a color may be defined as the light and shade in a color. Nature has a full scale of 100 values ranging from the deepest dark to the brightest light and every pigment has its own value, but with this difference that the rose color, for instance, like that in the corona which you get in pigment, will be much farther down in the scale of values. To get the rose color in pigment which would represent that of the corona, I experimented with the rose in the in the spectrum and finally arrived as near to that as possible.

My plan for the actual drawing was to sketch in the outline of the eclipse rapidly, jot down the color value present in the sky, moon, clouds, corona, hydrogen flames; each according to its numeric value in the scale, and after the eclipse was over fill them in at leisure. I did not bother with an accurate outline of sun and moon, preferring to depend on photographs for that. I used an easel protected by wind guards, white cardboard, and pencil, and with these I had ten drills preparatory to painting the eclipse.

When I came actually to do the sketch with the model posed before me for 112 seconds, I found I had ample time. I began with the sky, allotting ten seconds to that, then ten seconds for the moon and twenty for the corona, twenty for observation through the binoculars to survey the red prominences, and so on. When I got through I found I had jotted down these numbers at various points: sky, 30; clouds, 36; corona, 30–60; red prominences, 63; hydrogen flames, 70.

Two days later I was shown the negatives and the positives from photographs taken from the time, and with them and my own color observations, I painted the first drafts of my pictures.”

Review of Popular Astronomy, vol. 145–146 (1919)