Landscapes Paintings for Target Practice: Howard Russell Butler’s World War I Military Contribution

Juliana Ochs Dweck, Mellon Curator of Academic Engagement

Inspired by the landscape lithographs used for training by the British and French Armies, painted landscapes were adopted in the United States to help recruits judge topography from a distance during World War I rifle training. Princeton University was the first American college to use landscape targets and was especially dedicated to promoting the method. At Princeton, these oversized landscapes—bucolic martial tools—were painted by alumnus Howard Russell Butler.

As part of the University’s wartime military course—which enrolled students over the age of eighteen in a military or naval training unit, predating the founding of Princeton’s Army ROTC in 1919—students received instruction in signaling, topography, target practice, and musketry (known today as marksmanship or rifle training). To teach recruits to hone their aim, J. R. Cornelius, a Canadian Army captain and Princeton army instructor, relied on the new method called “landscape targets.” It was a form of visual training, as John Grier Hibben, Princeton University president from 1912 to 1932, described in 1919: “the recruit may be taught to recognize and aim at targets, such as folds in the ground, houses, trees, and other objects that would make an aiming mark in war.” The targets would teach sensitivity to distance and detail and also, according to Captain Cornelius, "color, shape, size, or movement.”

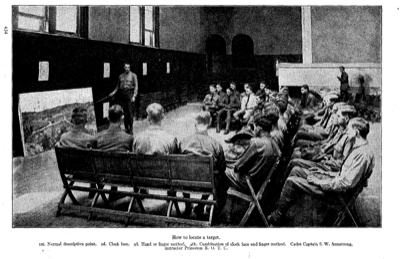

Working with Cornelius, Butler painted eight landscape targets in oil on canvas, extending up to thirty-nine feet. None survive, so we only know from photographs that the landscapes were usually used indoors, where they were placed on the floor to provide the sense of looking off into the distance. Soldiers would lie on the floor, each on his own thin mattress, head to the ground, eyes front, rifle extending out from his face. Sets of charcoal sketches of the landscape painting—that is, simulations of the painted scene—were mechanically raised and lowered after each round of firing, with the oil painting placed at least three hundred yards further back.

Whether we view Butler's landscape targets as artifacts of war or as war art, or somewhere between, we might consider them an early form of virtual reality. So accurately did Cornelius see the landscapes as simulating actual conditions that he said: “We have everything except atmospheric conditions and full-charge ammunition.” From scientific to architectural to military, Howard Russell Butler was always finding new applications for his art.