Timeline: Early Space Art

Ron Miller, author and illustrator; former art director of the National Air and Space Museum’s Albert Einstein Planetarium

Emile-Antoine Bayard (1837–1891) and Alphonse-Marie de Neuville (1835–1885)

The illustrations by Émile-Antoine Bayard and Alphonse-Marie de Neuville that accompanied Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon were the first attempts to depict realistically a space flight and the conditions that existed beyond Earth’s atmosphere. The realism is due as much to the excellent illustrators that Verne’s books invariably commanded as to Verne himself, who was in the habit of providing his artists with reference materials and checking the final results for authenticity.

Paul Dominique Phillipoteaux

In 1877, Verne’s novel Hector Servadac (perhaps better known as Off on a Comet!) contained illustrations by Paul Dominique Phillipoteaux (1846–1923), showing Jupiter and its satellites as seen from a passing asteroid and a view of Saturn’s rings as seen from the surface of that planet (probably the first such illustration attempted and arguably the first true example of astronomical art.)

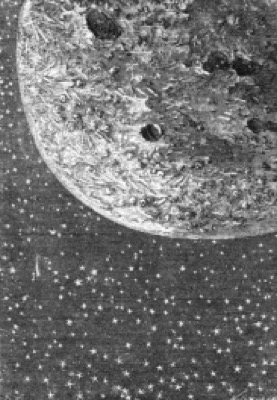

Camille Flammarion, Les terres du ciel, 1884

Paul Fouché, Motty, Blanadet, Hellé, and others

In 1884 the French astronomer/science popularizer Camille Flammarion published Les terres du ciel, the first of the three major landmarks of space art. This massive book contains hundreds of specially commissioned woodcut illustrations, created by a team of more than half a dozen artists. Principal among these are extraterrestrial scenes by Paul Fouché, Motty, Blanadet, Hellé, and others. These include views of the desolate landscape of Venus, the seas and mountains of Mars, and the crescent earth over the rugged lunar terrain.

Scriven Bolton (1888–1929)

The British amateur astronomer and artist Scriven Bolton (1883–1929) was probably the first artist to focus exclusively on astronomy. His innovative renderings—often employing detailed plaster models—appeared in numerous magazines and books on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the 1920s.

G. F. Morrell

In 1910, Morrell wondered what one might see if London were on Saturn. The original painting is titled If London Were on Saturn; The Magnificent Spectacle Presented by the Rings as Seen from Latitude 5.

G. F. Morrell, a contemporary of Bolton, not only created some splendidly expressionistic extraterrestrial landscapes but also made something of a specialty of showing what other worlds might look like if they were to replace the Earth’s moon.

Abbé Theophile Moreau (1867–1954)

The French artist Abbé Theophile Moreau, whose work first appeared in the late nineteenth century, had his astronomical renderings widely published. The director of the Observatory of Bourges, France, Moreau was the first of the astronomer-artists.

Lucien Rudaux (1874–1947)

A commercial artist turned astronomer, Rudaux was the first to specialize in astronomical illustration. Born in 1874, he eventually became one of the best observers of his day, working from his private observatory in Donville, France. He combined the results of direct observation with his skills as an artist to create some of the most scientifically accurate space paintings of his day. Indeed, many of his depictions of the moon, Mars, and the satellites of Saturn could just as easily have been done today.

Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986)

While not the first artist to specialize in astronomical art, Chesley Bonestell raised space art to the level of fine art. Always deeply interested in astronomy, Bonestell began creating space scenes for his own amusement. After the artist showed a series depicting Saturn as seen from its moons to the editors of Life magazine, his space art appeared in print for the first time in 1944. After several similar pictorials in Life and other magazines, Bonestell was lured back into motion pictures by George Pal. He created the fabulous 360-degree panorama of the lunar surface for Destination Moon, the opening sequence for War of the Worlds, and the matte paintings for When Worlds Collide. Around the same time, Bonestell was invited by Collier’s magazine editor Cornelius Ryan to participate in what would eventually become known as the “Collier’s Space Program.”

Frank R. Paul, Charles Schneeman Hubert Rogers, Charles Bittinger

Science-fiction magazines, the first of which was published in the late 1920s, were, interestingly enough, far ahead of more mainstream journals in publishing astronomical art. Many of these artists, such as Frank R. Paul, were unabashed in using Howard Russell Butler's paintings as inspiration for their own work. The artists who contributed some of the best realistic astronomical work included Charles Schneeman and Hubert Rogers (who created the first depiction of a gravitational lens). By comparison, the paintings provided by Charles Bittinger for National Geographic, though described as “combining a fine sense of color values and artistic composition with a painstaking effort to achieve scientific accuracy,” are for the most part crude and amateurish compared with the best that was being published in the science-fiction pulps or being done at that time by Rudaux.