The Princeton University Art Museum’s collection of photographs by Kenji Ishiguro (b. 1935)—which are rarely found outside of Japan—offers an informative lens through which to view the role of art in urban change. Ishiguro is best known for his postwar work of the 1950s and ’60s, when he lived and worked among Tokyo’s avant-garde. Ishiguro took these photographs in Tokyo between 1958 and 1960, during the dawn of Japan’s rapid economic growth. The photographs accordingly reflect a period of instability, rearrangement, and upheaval—not only of concrete and steel but also of ideas. The body of work depicts diverse subjects in disparate styles: artists, construction workers, student protesters, and streets are shown through fine-arts tableaux, photojournalistic works, or candid snapshots. For Ishiguro, using a camera was an act of recording and participating in the dismantling of prewar cities and prewar art. The works are organized into six themes:

- Construction

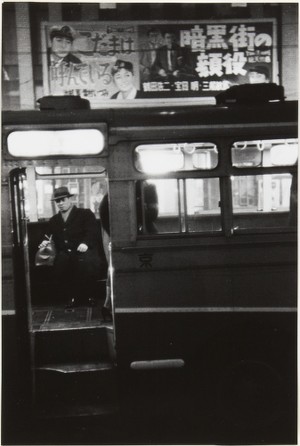

Kenji Ishiguro 石黒 健治, Japanese, born 1935 A Bus Passenger 1959 Gelatin silver print 24.8 x 16.6 cm. (9 3/4 x 6 9/16 in.) mount: 35.4 x 26.9 cm (13 15/16 x 10 9/16 in.) Gift of Robert A. Wayne, Class of 1960, by exchange 1996-91 - Decay

- Protest

- Arts

- Motion

- Still Tableaux

His wide variety of subject matter, lighting, and composition was part of a practice that he called “continuity through discontinuity.” Despite a seeming disjunction in style and subject from one photograph to the next, there is a unity to the collection as a coherent body of work. Ishiguro did not simply photograph views of the city’s changes but rather allowed the sometimes-unfavorable conditions of the city to affect the photographic apparatus itself. For example, the stillness of neglected places generated crisp, meditative exposures, while the movement of dancers, buses, and city streets could only be captured in a dramatic blur. Pictures taken in jazz cafés of young women, Neo-Dadaists, and musicians depict subjects with faces often obscured by hands, shadows, or cigarette smoke. The photographs present themselves as personal snapshots of private spaces, together forming a visual diary. The photographs of the protests, by contrast, are essentially journalistic, while the carefully composed tableaux of street scenes, such as At a Car-Washing Service (1959) or A Street (1959), are suggestive of art photography.

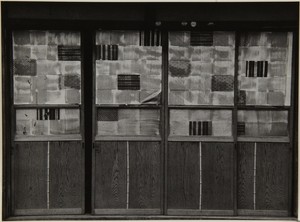

Altogether, Ishiguro’s images demonstrate a holistic engagement with the city—an engagement that includes not only studied compositions but also chance, low light, and moving, unreliable, unfamiliar subjects. In noticing the unsteadiness of the images and the compositional lines that are not parallel to the edges of the prints, one would suspect that the photographs were taken by an amateur without full control of the camera: see, for instance, A Bus Passenger (1959), A Building in Ginza (1959), or Boy with Hula Hoop (1959). However, Ishiguro identified worthy elements in the fuzzy negatives of these images, elements necessary to complete an accurate picture of a sometimes unstable urban environment. In stark contrast to his shaky exposures, the sharply defined photographs, such as A Street (1959), At a Car-Washing Service (1959), and A Street Corner (1959), provide quiet moments and reveal a rhythmic organization of shapes and grids, with neither motion nor people.

From the varied cityscapes, one can observe how Tokyo emphasized doing away with the old and building anew, thus allowing middle- and lower-class wooden structures to decay. Photographs such as the neon-lit A Man at Work (1959) or A Construction Gang (1959), with its large scale and bold contrast, juxtapose images of constructing the new, postwar city with quieter and more intimate images of neglect and disrepair, including the warped bamboo frames and torn screens of Sliding Doors in Asakusa (1958), the punctured paper and torn materials in A Street Corner (1959), or the thick, peeling palimpsests of advertisements, worn wood, and detritus in A Wall (1959).

Finally, the artist’s saturated, high-contrast snapshots from cafés, studios, and Zengakuren (a Japanese abbreviation of the All-Japan League of Student Self-Government) protests show a younger generation participating in new

Veronica Nicholson, Class of 2016