“A Single Drop of Ink for a Mirror”: Nineteenth-Century British Literature and the Visual Arts

With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader. —George Eliot, Adam Bede (1859)

In the opening lines of her first full-length novel, Adam Bede, George Eliot invites her reader into a story conjured out of the reflection of a single drop of penned ink. Later, she pauses her narrative to praise the aesthetics and aims of Dutch painting, which she feels is best equipped to depict the great multitude of faces of humanity. That she saw the best perspectives on the subject of everyday people as reflected in ink and paint clues us into the vital relationship between the two mediums in nineteenth-century Britain. This period witnessed an enormous proliferation of text and image, whether in the many illustrated periodicals that sprung up for an increasingly literate public or in the triple-decker novels that populated lending libraries across the country. Printmaking, drawing, painting, and photography flourished, and often borrowed themes and ideas from the literary world.

Supplemented by loans from the Princeton University Library and a private collection, this exhibition is shaped around the culture of text and image in nineteenth-century Britain, and reflects the stories, aspirations, and realities of the period. The prolific interaction of authors and visual artists during this time is demonstrated through a rich variety of objects, including bound and serialized editions of books by Charles Dickens, playing cards made in response to popular stories such as J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and works on paper by such author-illustrators as William Blake and Clare Leighton. Many of these pieces directly relate to an interdisciplinary conference on the relationship between literature and art in the nineteenth century (Princeton University, October 4–5, 2019).

Rosalind Parry, PhD 2018, Department of English, and Ariel Kline, graduate student, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University

-

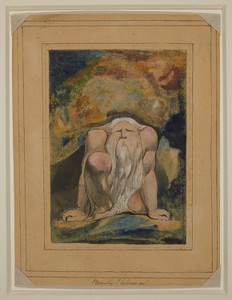

Eternally I labour on [Urizen, Plate 9 from Small Book of Designs copy B]

Eternally I labour on [Urizen, Plate 9 from Small Book of Designs copy B], 1794

Eternally I labour on [Urizen, Plate 9 from Small Book of Designs copy B], 1794 -

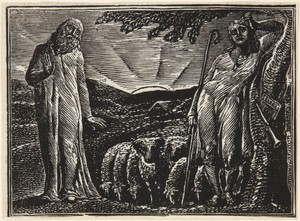

Frontispiece: Thenot and Colinet

Frontispiece: Thenot and Colinet, 1821

Frontispiece: Thenot and Colinet, 1821 -

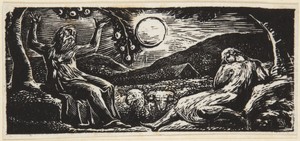

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet, 1821

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet, 1821 -

Thenot and Colinet Seated between Two Trees

Thenot and Colinet Seated between Two Trees, 1821

Thenot and Colinet Seated between Two Trees, 1821 -

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet; Lightfoot in the Distance

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet; Lightfoot in the Distance, 1821

Thenot Remonstrates with Colinet; Lightfoot in the Distance, 1821 -

Thenot, with Colinet Waving His Arms in Sorrow

Thenot, with Colinet Waving His Arms in Sorrow, 1821

Thenot, with Colinet Waving His Arms in Sorrow, 1821 -

Self-Portrait

Self-Portrait, ca. 1844

Self-Portrait, ca. 1844 -

Xit, now Sir Narcissus Le Grand entertaining his friends on his wedding day

Xit, now Sir Narcissus Le Grand entertaining his friends on his wedding day, 1840

Xit, now Sir Narcissus Le Grand entertaining his friends on his wedding day, 1840 -

The Minuet

The Minuet,

The Minuet, -

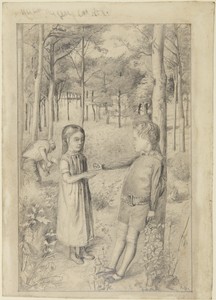

Study for The Woodman's Daughter

Study for The Woodman's Daughter, 1850

Study for The Woodman's Daughter, 1850 -

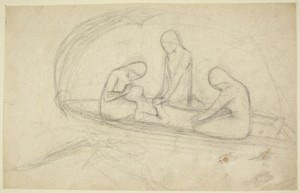

King Arthur's Death

King Arthur's Death, ca. 1859–62

King Arthur's Death, ca. 1859–62 -

Cover Design from A Portfolio of Aubrey Beardsley's drawings illustrating "Salome" by Oscar Wilde

Cover Design from A Portfolio of Aubrey Beardsley's drawings illustrating "Salome" by Oscar Wilde, John Lane, London, 1906–12

Cover Design from A Portfolio of Aubrey Beardsley's drawings illustrating "Salome" by Oscar Wilde, John Lane, London, 1906–12

- Page 1

- ››