Print as Political Statement: Lithography and the Popular Press

The development of the lithographic process marked a turning point in the production and distribution of political satire in the nineteenth century, considered the “golden age” of French caricature. Ongoing political upheavals demanded a printmaking medium that could correspondingly keep pace with the times. Lithographs are drawn with a greasy crayon directly onto a polished limestone slab that is processed and printed to make images that reproduce the original drawing. Easily adapted to mechanization, the technique was favored by caricaturists who were often expected to publish daily in illustrated journals. It was also used by artists such as Édouard Manet to create large-scale political commentaries as fine art prints. This selection of lithographs represents the scope of the artistic expression and the functions that lithography served in the nineteenth century.

Lithography became a pivotal mode of representation under King Louis-Philippe (reign 1830–1848), whose disappointing tenure as the “bourgeois monarch” was characterized by increasingly draconian press censorship laws. In spite of the censors, caricaturists continued to produce their prints, often facing fines and imprisonment. The subsequent presidency (1848–1852) and empire (1852–1870) of Napoleon III slightly relaxed these laws but never entirely allowed for unfettered publication.

Napoleon III’s ill-advised prosecution of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 - primarily rooted in competing imperial ambitions between the two countries - initiated nearly two years of devastation for the city of Paris. Convinced of military superiority, France declared war on Prussia in July 1870, only to suffer a string of rapid defeats culminating in the collapse of the French army and the capture of Napoleon at the Battle of Sudan on September 2, abruptly ending the Second Empire. A provisional Government of National Defense immediately declared the establishment of the French Third Republic and ineffectively continued the war with the remains of the army. By late September 1870, the Prussians had reached the outskirts of Paris and began a siege of privation that was to last four months. The capital finally fell when France surrendered the war on January 27, 1871. The financial and emotional losses incurred under the siege were chronicled in print, with caricaturists like Cham and Daumier vocal in their commentaries on the unrelenting violence and starvation facing Parisians.

With the government in exile in Versailles, the anger of Parisian working class socialists and political radicals over the war and unresolved grievances resulted in the formation of a Paris Commune that attempted to gain control of the city. The ensuing civil war left the city in ruins, with thousands of suspected communards exiled or massacred by government troops before order was restored. In the decades that followed, the memory of the revolt’s violent suppression remained within the artistic ethos in France.

Jessica Larson, summer intern, Ph.D. candidate, Department of Art History, University of Delaware

-

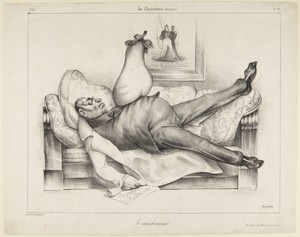

Le Cauchemar (The Nightmare)

Le Cauchemar (The Nightmare), published 1832

Le Cauchemar (The Nightmare), published 1832 -

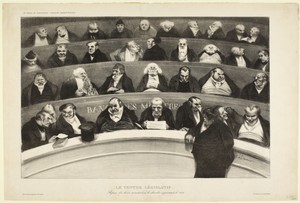

Le ventre législatif (The Legislative Belly), published in l’association mensuelle, January, 1834

Le ventre législatif (The Legislative Belly), published in l’association mensuelle, January, 1834, 1834

Le ventre législatif (The Legislative Belly), published in l’association mensuelle, January, 1834, 1834 -

Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril 1834, published in L’Association mensuelle, July 1834

Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril 1834, published in L’Association mensuelle, July 1834, 1834

Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril 1834, published in L’Association mensuelle, July 1834, 1834 -

No. 113, Après Le Siège (After the Siege), plate 39 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari

No. 113, Après Le Siège (After the Siege), plate 39 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari , 1870

No. 113, Après Le Siège (After the Siege), plate 39 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari , 1870 -

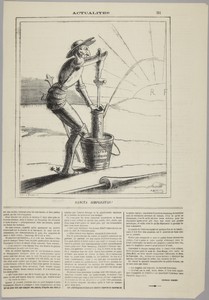

Sancta Simplicitas! (Sacred Simplicity), page 191 from Le Charivari, Actualités

Sancta Simplicitas! (Sacred Simplicity), page 191 from Le Charivari, Actualités, 1872

Sancta Simplicitas! (Sacred Simplicity), page 191 from Le Charivari, Actualités, 1872 -

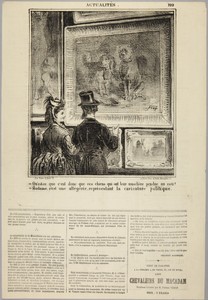

Qu’est-ce que c’est donc que ces chiens qui ont leur muselière pendue au cou ? (Why is it that those dogs have their muzzles hanging around their necks?), page 120 from Le Charivari, Actualités.

Qu’est-ce que c’est donc que ces chiens qui ont leur muselière pendue au cou ? (Why is it that those dogs have their muzzles hanging around their necks?), page 120 from Le Charivari, Actualités., after 1871

Qu’est-ce que c’est donc que ces chiens qui ont leur muselière pendue au cou ? (Why is it that those dogs have their muzzles hanging around their necks?), page 120 from Le Charivari, Actualités., after 1871 -

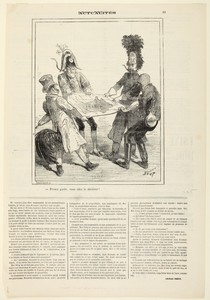

Prenez garde, vous allez la dechirer! (Be cafeful, you are going to tear it!), page 89 from Le Charivari, Actualités

Prenez garde, vous allez la dechirer! (Be cafeful, you are going to tear it!), page 89 from Le Charivari, Actualités, 1872

Prenez garde, vous allez la dechirer! (Be cafeful, you are going to tear it!), page 89 from Le Charivari, Actualités, 1872 -

11 Inch (27 tons) Gun, Mounted on Naval-Carriage

11 Inch (27 tons) Gun, Mounted on Naval-Carriage, 1869

11 Inch (27 tons) Gun, Mounted on Naval-Carriage, 1869 -

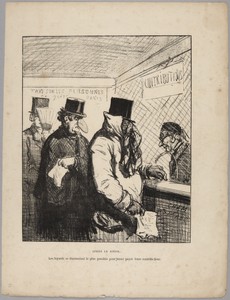

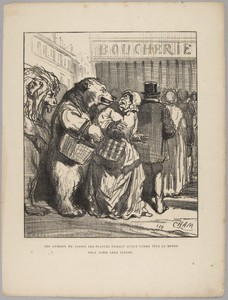

No. 110, Les Animaux du Jardin des Plantes Faisant Queue Comme Tout le Monde Pour Avoir Leur Viande (The animals from the Jardin des Plantes line up like the rest of the group in order to have their meat), plate 12 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari

No. 110, Les Animaux du Jardin des Plantes Faisant Queue Comme Tout le Monde Pour Avoir Leur Viande (The animals from the Jardin des Plantes line up like the rest of the group in order to have their meat), plate 12 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari, 1870

No. 110, Les Animaux du Jardin des Plantes Faisant Queue Comme Tout le Monde Pour Avoir Leur Viande (The animals from the Jardin des Plantes line up like the rest of the group in order to have their meat), plate 12 from Album du siège : recueil de caricatures publiées pendant le siège dans le Charivari, 1870 -

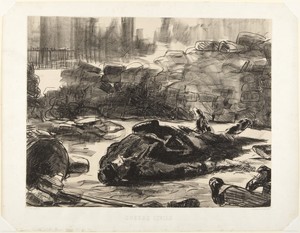

Guerre civile (Civil War)

Guerre civile (Civil War), 1871

Guerre civile (Civil War), 1871 -

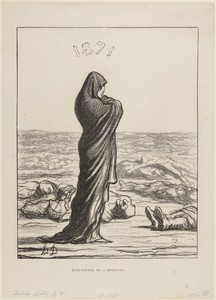

Épouvantée de l'héritage (Appalled by Her Legacy)

Épouvantée de l'héritage (Appalled by Her Legacy), 1871

Épouvantée de l'héritage (Appalled by Her Legacy), 1871 -

Au Mur, Episode de la Commune

Au Mur, Episode de la Commune, ca. 1871

Au Mur, Episode de la Commune, ca. 1871

- Page 1

- ››