Art@Bainbridge | Roberto Lugo / Orange and Black

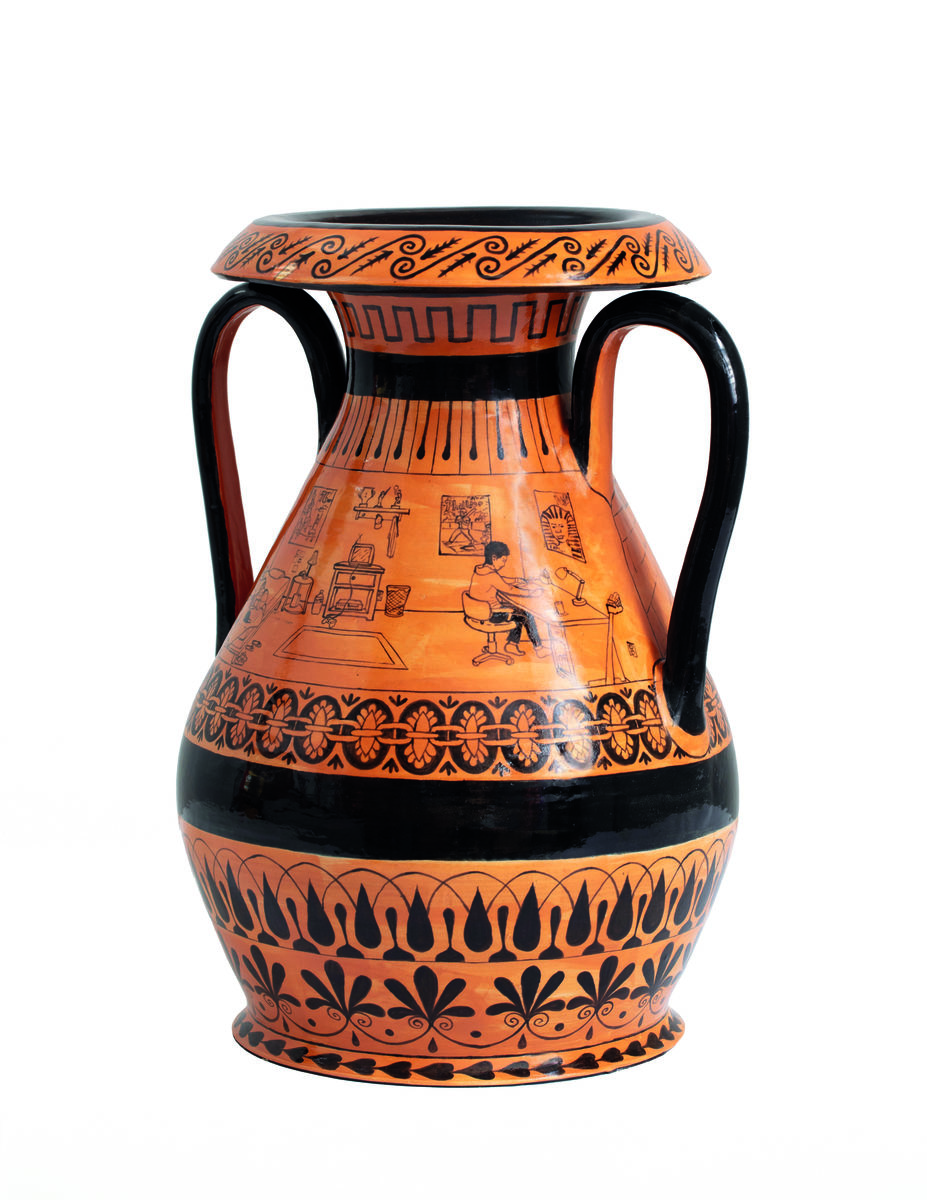

Lugo is a Philadelphia-based ceramic artist who takes inspiration from the forms and decoration of historical ceramic vessels, recontextualizing their visual imagery in his own work. In his recent series Orange and Black, Lugo draws on the shapes, techniques, and decorative motifs of ancient Greek vases to tell personal and communal stories, highlighting issues of oppression, inequality, racism, socioeconomic hardship, and incarceration. Adapting the pictorial narrative structures of ancient Greek objects, Lugo replaces the depiction of Greek life and myth with the underrepresented stories of people of color. He creatively plays with Athenian ornamental vase decoration to relate it to the imagery that pervades the present-day landscape of Philadelphia, creating a new mythology and visual vocabulary of life in America.

The work What Had Happened Was: The Path depicts the abolitionist Harriet Tubman leading a group of enslaved people to freedom and draws on ornament’s immersive invitation to the viewer to follow a repeating pattern as they move around the vessel. The visual narrative similarly progresses around the body of the vase, showing Tubman’s heroic efforts to save those oppressed by slavery and hinting at the seemingly never-ending struggle against inequality that so many continue to face today.

In preparation for the exhibition, a group of Museum staff visited Lugo’s studio to learn more about the artist’s process and technique. Vessels in various stages of completion were on view throughout the space, where he works with a team of artists to develop every aspect of a work. Lugo explained, “A lot of my process is improvisational, and I don’t know the full story that a work is going to tell.” Drawing on his own lived experience as well as on stories found on Greek and other historical vessels, Lugo considers in each instance “what a contemporary version of that thing would look like. It’s a full spectrum of ideas, and I figure out how to put all these things together so that it’s recognizable but also distinct.” He plays with the style and technique of red-figure painting that was developed in antiquity and molds it to tell his own narratives, whether by juxtaposing two parallel stories on either side of a vessel, continuing a narrative around the body of a vase, or drawing on actions and experiences that link the present with the past.

Describing his experience working on the exhibition, Lugo noted, “to have objects that are over a thousand years old, two thousand years old [alongside my own], it reminds me of when I got to see these pieces in [the Museum’s] storage—and I saw the way that the objects were made, and I saw throwing lines. And I just thought to myself, how profound it is that I’m making work in a tradition that’s so many generations old, and so many things have happened since then. To be able to be in that room makes me feel like I did something important with my life, that regardless of whether people know or not who I am after I pass, the things that I’ve made and the stories that I’ve told will exist.”

Carolyn Laferrière

Associate Curator of Ancient Mediterranean Art

Art@Bainbridge is made possible through the generous support of the Virginia and Bagley Wright, Class of 1946, Program Fund for Modern and Contemporary Art; the Kathleen C. Sherrerd Program Fund for American Art; Barbara and Gerald Essig; Gene Locks, Class of 1959, and Sueyun Locks; and Ivy Beth Lewis.

Additional support for Roberto Lugo / Orange and Black is provided by the Curtis W. McGraw Foundation; the Edna W. Andrade Fund of the Philadelphia Foundation; and Princeton University’s Humanities Council, Program in Latin American Studies, Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies (with the support of the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund), Department of African American Studies, Graduate School—Access, Diversity and Inclusion, Effron Center for the Study of America, and Program in Latino Studies.